The Living Structure: Why the Future of Concrete Is Alive

What if the buildings we live and work in were less like static objects and more like living organisms?

It sounds like a concept from a science fiction novel, but it is a necessary evolution for the most common building material on Earth. We use concrete for almost everything, yet we have traditionally accepted a major flaw: it is guaranteed to crack. Whether it is because the ground shifts or the material shrinks as it dries, these fractures are an inevitable engineering headache.

The real problem isn't just the appearance of a crack, but what happens when water finds its way inside. Once moisture reaches the steel bars reinforcing the concrete, those bars begin to rust. As they rust, they expand and put immense pressure on the concrete from the inside out (a process often called concrete "disease"). This eventually causes the entire structure to fail.

Fixing this manually is a massive burden. It is expensive, labor-intensive, and carries a heavy carbon footprint. However, material science is now using biology to do the maintenance work for us.

The Science of Bioconcrete

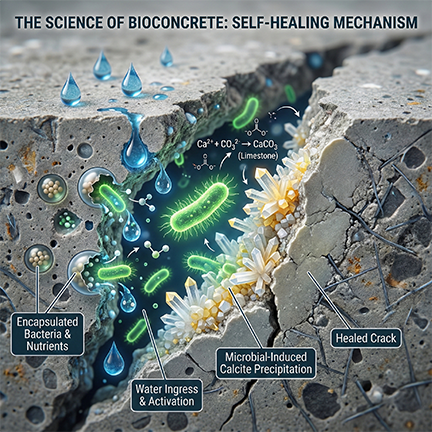

Self-healing concrete, or bioconcrete, is the result of mixing structural engineering with microbiology. A team at Delft University of Technology, led by Henk Jonkers, realized they could bake "repairmen" directly into the material. When the concrete is mixed, they add two key components:

Bacterial Spores: These come from the Bacillus group. They are chosen because they can survive in the harsh, high-alkaline environment of concrete. In their spore state, they can stay dormant (essentially a deep sleep) for up to 200 years without food or oxygen.

Calcium Lactate: This is a nutrient source (a type of salt) that acts as the "food" for the bacteria once they are triggered.

The Awakening: How It Works

The bacteria remain completely inactive as long as the concrete is solid. But the moment a crack forms and water seeps in, it acts as a biological wake-up call. The moisture dissolves the packaging around the spores and "wakes" the bacteria.

Once active, the bacteria consume the calcium lactate and, through a natural chemical reaction, excrete calcite. This calcite hardens into limestone, which builds up until the crack is sealed. Lab tests show this can repair cracks up to 0.8 mm wide in just a few weeks. It is a brilliant bit of logic: the material uses the very water that would usually destroy it to trigger its own recovery.

Why This Matters

This isn't just a clever science experiment; it is a vital tool for sustainability. Cement production is responsible for roughly 8% of global carbon emissions. If we can extend the life of a bridge, tunnel, or foundation by 20 or 30 years, we don't have to produce nearly as much new cement. This allows the industry to focus on preserving what we already have instead of constantly rebuilding.

The Reality Check

If this technology is so effective, why isn't every new building using it? To be blunt, it comes down to the bottom line. Bioconcrete is expensive, often costing about double the price of traditional mixes. Most developers are focused on the immediate construction budget rather than the maintenance savings they might see twenty years down the road.

We also have to be realistic about the physical limits. This technology is designed to seal micro-cracks and protect the internal steel from water. It is not a miracle cure for structural failure. If a foundation shifts significantly or a major support beam snaps, a few bacteria aren't going to save the day. It is a tool for durability, not a substitute for sound engineering.

Conclusion

Bioconcrete forces us to rethink our built environment. Instead of seeing buildings as cold, dead objects, we can begin to view them as living systems. By integrating biology into architecture, we create structures that can actually respond to their surroundings and repair themselves when things go wrong.

What if the buildings we live and work in were less like static objects and more like living organisms?